Before “Pokemon Go,” there was another group of people with a drive to catch ‘em all—naturalists obsessed with catching and cataloging as much of Earth’s rich biodiversity as possible. But how did women scientists fit into that mix during their earliest days in the field? Pamela M. Henson explores—and learns that tensions between men and women raged hard as women entered previously-forbidden scientific territory between 1900 and 1950.

As women increasingly entered biology, explains Henson, they began to conduct fieldwork in Latin America in a bid to categorize or study organisms that were either endemic to or had migrated to the region. But there was a problem for these pioneering women scientists: Popular culture painted both the tropics and the field as too wild, too remote, and too uncivilized for women. When organizations like the Smithsonian Institution sponsored a large-scale expedition to Panama in the early part of the 20th century, for example, women were precluded from participating.

By the 1920s, though, women finally pushed their way into newly-built field stations for scientific research like Panama’s Barro Colorado Island. Scientists on the island lobbied against calls to create a women’s dormitory and women had to stay on the mainland for over two decades while they conducted fieldwork there. Jealous and threatened, scientists refused to let women view the work conducted on the island, called for the exclusion of female bird watchers, and generally fought to exclude them from the field.

Henson documents the many reasons men claimed they objected to women on the island, from fears that they would object to procedures like vivisection to claims that they would lower the level of intellectual discourse or encourage men to act immorally to objections to their “non-professional” status. Ironically, the island was also closed to Latin American scientists.

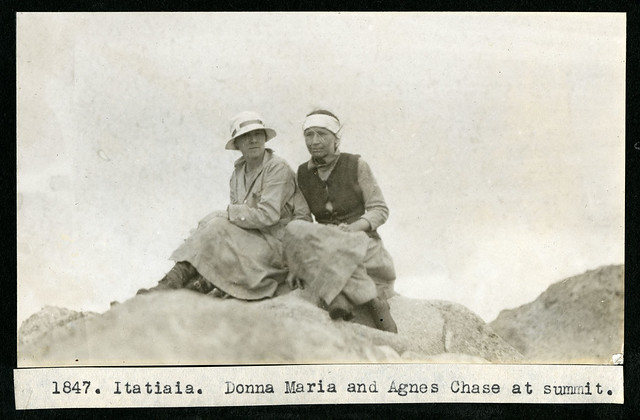

Excluded from fieldwork by the fear and prejudice of their male colleagues, some women who were determined to work in the field teamed up with Latin American scientists instead. Mary Agnes Chase, a renowned botanist who specialized in grasses, forged connections with her colleagues throughout Latin America by letter. After failing to do research in Panama, she used those relationships, and ones she formed with female missionaries, to take multiple solo trips to Brazil. “Denied access to institutionally supported fieldwork,” writes Henson, “Chase broke through the barriers and established more informal and egalitarian ties with Latin American scientists than many of her male colleagues ever had.”

Today, 58 percent of all bachelor’s degrees in biology go to women, and fieldwork is a critical part of both undergraduate and graduate education for women. But fieldwork is still a fraught topic for women in science: In 2014, a survey of over 600 women who perform fieldwork found that 64 percent of women had been sexually harassed in the field and that 22 percent—more than one in five–were assaulted in the field. Women may have finally “invaded Arcadia,” in the words of Henson, but they have yet to achieve full equality or safety there.

Extra: See more of Mary Agnes Chase’s specimens and correspondence on JSTOR Global Plants.