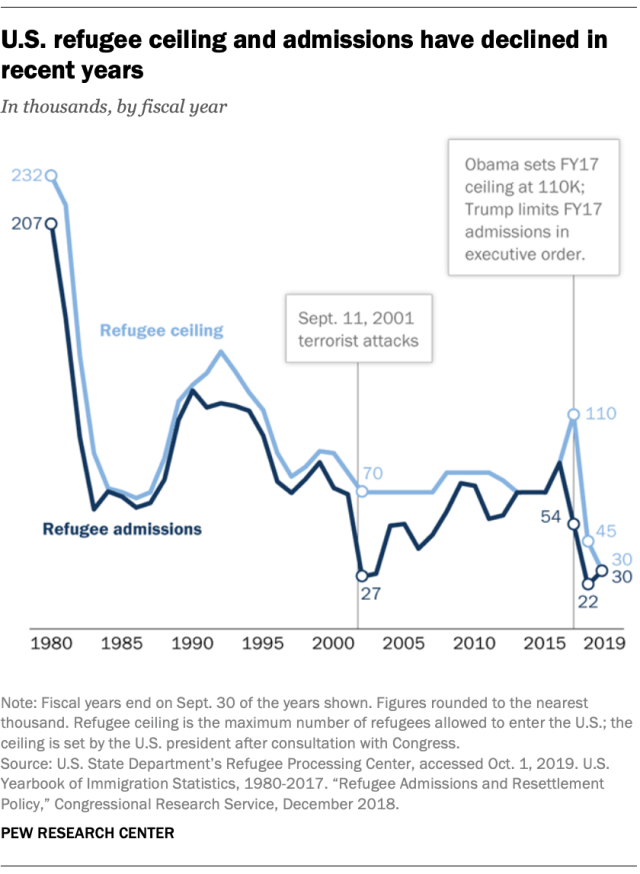

In the fall of 2019, the White House announced its plan to cap 2020 refugee admissions at 18,000 people. That figure represents the lowest since the country’s modern asylum system was created in 1980, and follows a steady pattern of erosion since President Donald Trump took office. The ceiling was set at 45,000 in 2018, and 50,000 in 2017, each a record-setting low.

The 1980 Refugee Act formalized refugee policy for the first time, broadening it to encompass a range of persecuted persons. As Jana K. Lipman, an associate professor of History at Tulane University, writes in At War (Rutgers UP 2018):

…refugee policy was intimately tied to Cold War politics and immigration restriction. The United States defined most refugee claims through the prism of anticommunism, and as a result, those fleeing communist countries were most likely to be admitted.

Throughout the decade, Lipman notes, an escape from communism, not atrocity, was frequently used as the benchmark in evaluating claims, with a racial element playing no small role. While more than 100,000 Cubans were permitted entry into the U.S. during the Mariel boatlift, in 1980, Haitians fleeing their own brutal (though avowedly anticommunist) government in the year after, were stopped at sea. They were given “cursory asylum hearings, and then returned… to Haiti at a rate of almost 100 percent.”

That situation continued well into the 1990s, when Cubans continued to be admitted to the U.S., while Haitians fleeing the violence borne from a coup against Jean-Bertrand Aristide were deemed “economic migrants” and granted asylum at a fraction of the rate. Lipman explores the consequences of these designations, which have echoes in our refugee policy to this day. What makes a “good” refugee? Who is an “economic migrant” and who an “illegal alien?”

The makings of our modern resettlement system can be traced back to the fallout of the Vietnam War, a cascade of international crises stoked by the U.S. Starting in the mid-1970s, hundreds of thousands of “Indochinese” refugees poured out of Laos, Vietnam, and Cambodia, escaping newly installed brutal communist governments, ethnic repression, retribution against American allies, starvation, war crimes, and genocide.

Last year marked 40 years since the fall of the Khmer Rouge. An estimated 1.7 million people died under the Khmer Rouge: starved, overworked, murdered. That is equivalent to about a quarter of the population at the time, meaning virtually no Cambodian family is untouched even to this day. In Cambodia, the three years, eight months, and 20 days that the Khmer Rouge officially held power shaped the country that was to come. In the U.S., the depth of the horrors, coupled with the U.S.’s role in them, ended up shaping our refugee policy—and the modern understanding of who, exactly, is “deserving” of asylum.

The radical state of Democratic Kampuchea “has been labeled Marxist-Leninist, Maoist, peasant-populist, national chauvinist and even fascist by various observers of Cambodia,” Kate Frieson wryly notes in a 1988 article in Pacific Affairs. “The enigmatic character of Democratic Kampuchea resists typological analysis.” Its leaders, who grew entranced by Marxism as students in Paris in the 1950s, and by Mao in later years, created a system with scant historical antecedent. The system was agrarian and centered on the idea of Khmer self-sufficiency. Unlike with Marxism, however, there was no evolution of steps. When the Khmer Rouge took over, there was simply an immediate and unprecedented destruction of every standing system at once.

When Phnom Penh fell to the Khmer Rouge on April 17, 1975, the regime emptied the city of more than 2 million residents. The process moved so quickly that patients were abandoned in hospitals, and pregnant women died in labor on the side of the road. The evacuation of Phnom Penh was unprecedented in scale, but it was mimicked across the country. People were forced from their homes; sorted into groups of “new” and “base” people (with punishment meted out to the educated urbanites, who were seen as societal consumers rather than contributors); and rearranged into a system of agricultural collectives and infrastructure work camps. Religion, government, currency, and family bonds were ordered immediately dissolved. The leadership, known only as Angkar, or “organization,” insisted that this was the first step to a truly self-sufficient nation.

The overthrow, of course, did not happen in a vacuum. In the preceding years, a so-called secret bombing campaign by the Americans devastated a neutral Cambodia. Secret to whom? Certainly not those suffering the impact. Even today, the countryside is littered with ponds and craters, the remnants of bombs showered down by B-52s. Some 500,000 tons of explosives were dropped on Cambodia, with the aim of cutting off North Vietnamese supply lines. Hundreds of thousands of Cambodians were killed, villages were destroyed, and the agriculture-based economy collapsed. As the political and economic turmoil worsened, a coup overthrew prime minister Norodom Sihanouk, the mercurial but beloved king who abdicated the throne to enter politics.

Sihanouk was replaced by a corrupt, U.S.-backed general named Lon Nol, and the country quickly devolved. Farmers fled the bombings for the capital, the economy continued to plunge, and Sihanouk—fatefully—aligned himself with the Khmer Rouge, giving the guerillas wider support. Civil war between the Khmer Rouge and Lon Nol’s government gained strength, sending more refugees fleeing. As the Khmer Rouge moved closer to Phnom Penh, the U.S. cut off military aid and foreign embassies began evacuating. When the regime finally took the capital on April 17, 1975, many celebrated, if only for a very brief moment. After eight years of civil war, this, they believed, represented the end to violence, fear, and hunger.

While it is commonly said that the horror of Khmer Rouge wasn’t truly understood until after its fall, in 1979, that is not the whole truth. In 1973, Kenneth Quinn, a junior officer in the American foreign service based in Saigon, stood on a hill near the Cambodian border and watched in horror as the Khmer Rouge systematically razed villages “to force every citizen of that small region from their homes and into the jungle to build a new, harsh existence,” he recounted years later. Quinn began interviewing refugees fleeing those border areas and, in an impassioned report sent to Congress the following February, shared his findings in no uncertain terms. “The Khmer Krahom’s programs have much in common with those of totalitarian regimes in Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union, particularly regarding efforts to psychologically reconstruct individual members of society.”

Journalists writing in 1974 and 1975 detailed what had begun happening in villages occupied by the Khmer Rouge. Even after the country went silent, news reports emerged from the borders to which refugees were fleeing, including a large scale investigation by Time in 1976. Congress took testimony from activists, who had a remarkably thorough grasp of the situation on the ground.

In a paper for Diplomatic History, Kenton Clymer, a Distinguished Research Professor of History at Northern Illinois University, outlines just how extensive the public record was—and the impact it had (albeit painfully late) on U.S. government policy. Months before the Khmer Rouge was to fall, in October, 1978, Congress passed resolutions to allow 15,000 Cambodian refugees into the U.S. When the regime did fall, on January 7, 1979, hundreds of thousands of Cambodians began fleeing to vast border camps, and the full extent of the Khmer Rouge machine appeared. In 1980, Congress raised the quota for refugees to more than 230,000 and admitted 207,000, the vast majority of them from Southeast Asia.

In some ways, the barbarism of the Khmer Rouge was truly unique; in others, it is painfully familiar. Globally, there are nearly 71 million forcibly displaced peoples, the highest figure in history, and one that rises by the year. In China, an estimated tenth of the Muslim Uyghur minority has been rounded up into euphemistically named “re-education camps,” in which torture and rape appear to be widespread. In Bangladesh refugee camps, one million Muslim Rohingya, who fled a rampaging military campaign in their native Myanmar, desperately await a path home. Refugees fleeing ISIS in Iraq and Syria carry with them stories of carnage. In El Salvador, drug cartels have terrorized communities and made the country the world’s deadliest.

As with the Khmer Rouge, some of the underlying instability can be traced back to U.S. policies. Unlike in 1980, however, there is scant government effort to bring those most impacted by these conflicts or crimes under U.S. care. The hundreds of thousands of Central Americans fleeing brutal violence have been met with the harshest border control in American history. U.S. wars and U.S. military actions in the Middle East continue to contribute to the unparalleled displacement of people, but the country has accepted just a tiny fraction of the total number of refugees. With climate change making larger swathes of the world unlivable by the year, hundreds of millions more will have to move. Again, this past year, the refugee quota was set at 30,000—the lowest ceiling since the passage of the Refugee Act in 1980. And again, on November 1, 2019, the White House announced that in 2020, that figure will drop to 18,000.

The American trend is hardly unique. Across the globe, nations are tightening borders and turning to drastic efforts at deterrence—doing everything in their power to prevent refugees from showing up to seek asylum in the first place. Perhaps the starkest example of this is Australia’s Pacific Solution, in which any asylum seeker arriving by boat is automatically barred from seeking asylum and detained indefinitely in an offshore processing center—in violation of international law.

In an exploration in the Columbia Law Review of the impact of refugee deterrence on civil liberties, Eric A. Ormsby writes:

The proliferation of different refugee deterrence policies over the past three decades, as well as the increasing sophistication of these policies, reflects an increasing sense among many countries that the duties they bear toward refugees are a significant burden. What is far from clear, however, is whether the policies have achieved their desired effects; indeed, the very fact that many states have felt compelled to pursue ever-more restrictive and elaborate policies can be seen as persuasive evidence that they have not.

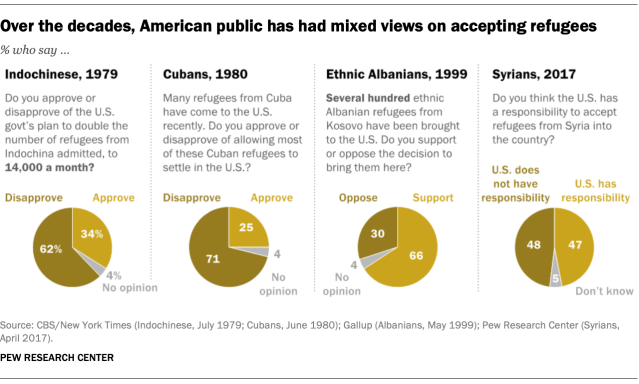

Public attitudes toward immigration have shifted as well, though not in the way one might anticipate. While the specter of “illegal” immigration has become a catch-all for many of those with legitimate asylum claims, far fewer Americans today support a decrease in legal immigration than did 50 years ago. What opinion polls show, most starkly, however, is how willing the government has been to buck public opinion entirely. In 1980, during the Cuban boat crisis, 71 percent of the population opposed allowing Cuban refugees to resettle in the U.S. One year earlier, as the government prepared to bring in tens of thousands of Vietnamese and Cambodian refugees—doubling the number admitted—just 34 percent were in favor of the decision. In 1975, as Saigon and Phnom Penh fell, just weeks apart, only 37 percent supported the refugees coming to the U.S.

Today, the refugee crisis lies far closer to home. But, in spite of the politicking, Americans increasingly approve admission of Central American asylum seekers: in the last Gallup poll, taken in August, 57 percent supported entry, an increase from six months earlier.